"It was late at night, and a fine rain was swirling softly down, causing the pavements to glisten with hue of steel and blue and yellow in the rays of the innumerable lights. A youth was trudging slowly, without enthusiasm, with his hands buried deep in his trousers' pockets, toward the downtown places where beds can be hired for coppers. He was clothed

in an aged and tattered suit, and his derby was a marvel of dust-covered crown and torn rim. He was going forth to eat as the wanderer may eat, and sleep as the homeless sleep.

By the time he had reached City Hall Park he was so completely plastered with yells of "bum" and "hobo," and with various unholy epithets that small boys had applied to him at intervals, that he was in a state of the most profound dejection. The sifting rain saturated the old velvet collar of his overcoat, and as the wet cloth pressed against his neck, he felt that there no longer could be pleasure in life. He looked about him searching for an outcast of highest degree that they too might share miseries, but the lights threw a quivering glare over rows and circles of deserted benches that glistened damply, showing patches of wet sod behind them. It seemed that their usual freights had fled on this night to better things. There were only squads of well-dressed Brooklyn people who swarmed towards the bridge."

From An Experiment In Misery

Wardipedia Entry #001-L

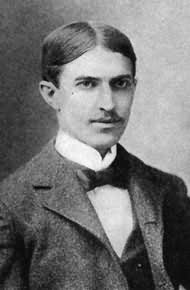

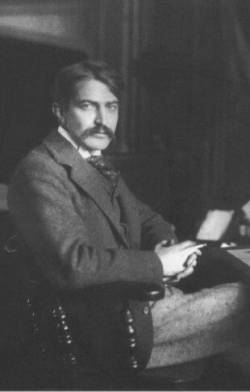

Stephen Crane (1871-1900)

I had planned to write something about Stephen Crane, my alltime favorite 19th Century American writer, for a few weeks now, had made all kinds of notes in my little spiral pocket notebook, yet until just a few minutes ago I had not realized that yesterday (November 1) was his birthday. Amazing. Had he not died at age 28 in 1900, he would have been 135 years old yesterday, with a much more impressive body of work to his credit. I'm sure that's of little consolation to him now.

I saw Crane's work as a bridge to the 20th Century. No accident that he died right on the cusp of the modern age. He passed on the tools that would enable other writers to create a new social realism equpped to deal with the manifold challenges of a new era.

But it was always Crane the Man more than just the Writer that intrigued me. In such a short period of time (even tragic Ed Poe lived to 40), Stephen Crane was startlingly prolific, managing to make his mark as a reporter, war correspondent, freelance writer, poet, essayist, novelist, writer of short stories, Westerns, Easterns... The most apt comparison might be Jack London, but London also lived to 40, a full 10 years longer than the short-lived, restless Crane, the youngest of 14 childre

n born in Newark, New Jersey, to a Methodist minister.

n born in Newark, New Jersey, to a Methodist minister.Crane spent the last years of his brief, productive life on a country estate in England, where he was visited and befriended by some of the best and most famous writers of the time, including giants like Henry James, Joseph Conrad, and H.G. Wells, who perceived greatness in Crane at a time when he was largely neglected.

"The one thing that deeply pleases me is the fact that men of sense invariably believe me to be sincere. I know that my work does not amount to a string of dried beans -- I always calmly admit it -- but I also know that I do the best that is in me without regard to praise or blame. When I was the mark of every humorist in the country, I went ahead; and now when I am the mark for only fifty per cent of the humorists in the country, I go ahead; for I understand that a man is born into the world with his own pair of eyes, and he is not at all responsible for his vision -- he is merely responsible for his quality of personal honesty. To keep close to this personal honesty is my supreme ambition." (Stephen Crane)

Underappreciated in his own country (even his American Civil War masterpiece, The Red Badge of Courage, first hit it big in England when it was championed by the British critical press before becoming hugely popular in America), unable to support himself with his writing, dying of tuberculosis, Crane himself perhaps would have never imagined the critical rebirth he would undergo nearly a century later -- rightly credited as one of the forerunners of what later came to known as Literary naturalism. He bravely forged a unique style combining gritty realism with impressionistic flourishes of description -- famously manifesting itself in the use of great visual bursts of color he took from the artists and painters he spent time with.

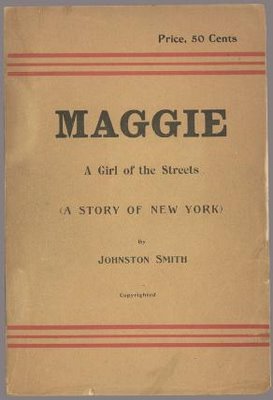

His first major work, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, was published at his own expense in 1893 under the pseudonym Johnston Smith, with most of the 100 or so copies printed lat

er burned in a fit of frustration. Ahead of his time for the first but not the last time, Maggie contained perhaps a little too much realism for the period, unflinchingly chronicling the descent of a street prostitute -- a morality tale that blamed not just the victim but, tellingly, the economic circumstances and social environment that contributed to her downfall -- told in equal parts Greek tragedy, Twain-ian black humor, Russian social realism, Dickensian empathy, with perhaps just a dash of Marxist foreboding.

er burned in a fit of frustration. Ahead of his time for the first but not the last time, Maggie contained perhaps a little too much realism for the period, unflinchingly chronicling the descent of a street prostitute -- a morality tale that blamed not just the victim but, tellingly, the economic circumstances and social environment that contributed to her downfall -- told in equal parts Greek tragedy, Twain-ian black humor, Russian social realism, Dickensian empathy, with perhaps just a dash of Marxist foreboding.Crane managed to pack an enormous amount of quality work into what amounts to something less than a full decade: he wrote Maggie in 1893; Red Badge and his first book of poetry, The Black Riders, in 1895; collections of short stories, war dispatches from Greece, Mexico and Cuba in 1898; another book of poems, War Is Kind, and the Whilomville Stories, tales of smalltown life, published in 1899. In addition, there were the magazine features, novellas and some of the greatest short fiction on the closing of the American West ever captured on paper.

Born 10 years after the start of the Civil War, Crane relied on veterans' accounts of major battles for his incisive masterpiece on the senseless violence of war and the meaning of courage, cowardice, heroism and identity. These recollections were supplemented by further research and reading and then forged with something less tangible but just as significant: the psychological and emotional stress he remembered from the hard-fought football games of his youth. It was his success in capturing the realism of the battlefield, despite having never seen live combat, that led to his being hired as a war correspondent by some of the leading publications of his day, where he displayed such grace and courage under fire that it was noted by seasoned journalists.

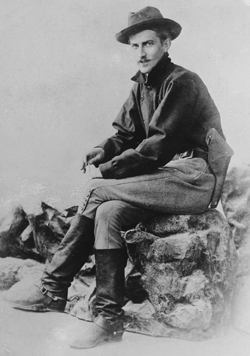

For the short stories An Experiment In Misery and The Men in the Storm, Crane went undercover as a "hobo," sleeping in a flophouse to learn firsthand how the impoverished and homeless felt living in the shadow of the great wealth of New York City -- something few other writers of the time not named Jacob Riis seemed to be expending great energies on.

For his pioneering efforts in free verse poetry he was rewarded with his being the subject of satire, parody and excoriation by mainstream critics. In search of adventure and the frontier he had read about as a boy, he went West and, not finding it, came back disillusioned, which fueled some of his best work, such as The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky and The Blue Hotel. The experience of almost drowning in a shipwreck off Cuba was background for perhaps his most technically proficient work, the superb short story The Open Boat, with its memorably stark opening line, "None of them knew the color of the sky."

"I decided that the nearer a writer gets to life, the greater he becomes as an artist, and most of my prose writings have been towards the goal partially described by that misunderstood and abused word, realism. Tolstoi is the writer I admire most of all. I've been a free lance during most of the time I have been doing literary work, writing stories and articles about anything under heaven that seemed to possess interest, and selling them wherever I could. It was hopeless work. Of all human lots for a person of sensibility, that of an obscure free lance in literature or journalism is, I think, the most discouraging. It was during this period that I wrote The Red Badge of Courage. It was an effort born of pain -- despair, almost; and I believe that this made it a better piece of literature than it otherwise would have been. It seems a pity that art should be a child of pain, and yet I think it is. Of course, we have fine writers who are prosperous, but in my opinion their work would be greater if this were not so. It lacks the sting it would have if written under the spur of a great need." (Stephen Crane)

Stephen Crane also played shortstop and was captain on the varsity baseball team while a Freshman at Syracuse University. He hung out with Impressionist painters at the Art Students League and with other like-minded bohemians in New York City. He notoriously came to the rescue of a prostitute who he thought was being unfairly arrested, an escapade leading to a court appearance which received the full tabloid treatment in the gossip pages and more unwanted publicity. He married a brothel owner he met in Florida. He was rumored to have smoked opium on a few occasions so that he could capture with verisimilitude the life of a drug addict for a feature article called Opium's Varied Dreams.

With all this literary material, and given that his life story has such undeniable cinematic appeal, I have often wondered why no movie was ever made of Stephen Crane's life and times. I mean, we have two Truman Capote filmic treatments, as well as recent flicks on writers as different as Virginia Woolf and Charles Bukowski, but still no love for Stephen Crane. C'mon Hollywood, get on the ball here. All you indie guys, what are you waiting for? At this point I'd even settle for a Bollywood musical.

Let's get something straight. I'm here to throw out the ideas. I'm too busy right now to follow up on most of them -- you saw my blog -- but what's your excuse? How about Colin Farrell for the lead? He's played almost every other historical figure in recent years. Or maybe Russell Crowe. I'm brainstorming here, people...

Of course, Red Badge was made into a movie on several occasions, most successfully in the 1951 film directed by John Huston, joining All Quiet on the Western Front as one of the great book-to-screen antiwa

r classics.

r classics. I own about 10 different editions of Red Badge, picking copies up whenever I come across one in a used bookstore. But the one book I would track down if I ever became a rare book collector is that first edition "vanity press" Maggie from 1893. Who knows how many copies are still extant. I do have a 1933 First Modern Library Edition Maggie, though, a little pocket-size book I bought at the Strand for $2 in 1982, according to the little yellow sticker still on the inside cover. It's got a faded blue cover and it's worn and torn in more than a few spots, but it's something I treasure.

Let me leave you with this prescient passage from the end of 1894's An Experiment in Misery, which like a lot of Crane's best work still holds up well to this day:

"In City Hall Park the two wanderers sat down in the little circle of benches sanctified by traditions of their class. They huddled in their old garments, slumbrously conscious of the march of the hours which for them had no meaning.

The people of the street hurrying hither and thither made a blend of black figures, changing, yet frieze-like. They walked in their good clothes as upon important missions, giving no gaze to the two wanderers seated upon the benches. They expressed to the young man his infinite distance from all he valued. Social position, comfort, the pleasures of living were unconquerable kingdoms. He felt a sudden awe.

And in the background a mulititude of buildings, of pitiless hues and sternly high, were to him emblematic of a nation forcing its regal head into the coulds, throwing no downward glances; in the sublimity of its aspirations ignoring the wretches who may flounder at its feet. The roar of the city in his ear was to him the confusion of strange tongues, babbling heedlessly; it was the clink of coin, the voice of the city's hopes, which were to him no hopes.

He confessed himself an outcast, and his eyes from under the lowered rim of his hat began to glance guiltily, wearing the criminal expr ession that comes with certain convictions."

ession that comes with certain convictions."

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment